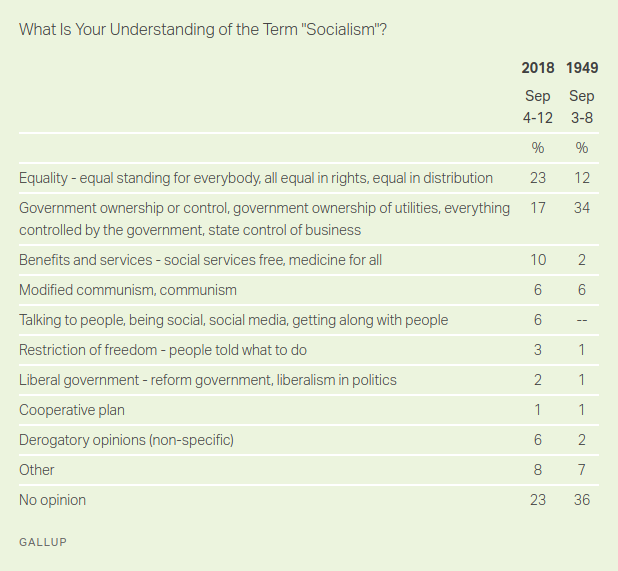

In 2018, Gallup conducted a poll to learn what most people in the US think of when they hear the word “socialism.” The poll compared responses in 2018 and 1949, and pointed out a big change in perception over the seven decades since the beginning of the Cold War.

One of the most interesting findings is that over that time there has been a shift away from considering socialism to mean “state control of business” to meaning “equality” and “benefits and services.” The old perception (despite being incorrect, see below) made a lot of sense in relation to the main model of socialism that existed in the world at that time—the centrally planned, government-run economies of Russia and China. The new perception is much better aligned with the current understanding of socialism in Western European and South American democracies—of a country where everyone in society gets equal access to the kinds of benefits and services that increase the well-being of society as a whole.

I largely agree with the perception of socialism as a more fair distribution of the goods of society, but it wasn’t until just a few years ago that I learned the actual definition of socialism. And while the perception is measurably changing1, I’ve encountered many people (particularly online) who, just as I used to do, incorrectly identify socialism in terms of a centrally-planned bureaucratic government that tries to control everyone’s lives and thoughts.

As it turns out there is a school of thought specifically dedicated to describing how socialism would work hand-in-hand with competitive markets. So to better explain what socialism is, I’d like to describe some of the main principles of the socio-economic philosophy called market socialism.

Market Socialism in a Nutshell

Market socialism preserves the market society that we’ve come to rely on— one where people trade goods and services using money, but it changes one crucial detail. Ultimately the difference between the two systems is only a question of framing our relationship to ownership of businesses, natural resources, and investments. Under capitalism the ownership of our economy belongs to those with great wealth, and they generally hire (poorer) working people to do work and manage the resources they own. By contrast, under market socialism, ownership is transfered to society as a whole, with different institutions set up as the stewarding bodies of that ownership.

I’ll get into more detail about how this has taken shape before and how it could in the future because there are myriad different ways that this takes place. But no matter how this takes place there is always only one fundamental change in the economy, which is who owns it. To understand what this change in fundamental ownership means, we need to break down ownership into its two core pieces: control and the right to profit.

Control

Having ownership over a business or resource implies that one has control over how it gets used. Owners get to decide ultimately what is done with their property. This control is already regulated by society in ways that prevent owners from doing things that would be massively detrimental, like polluting or creating destructive weapons, but market socialism would take the degree of societal control further.

Under a market socialist system, the ultimate ownership of natural resources or business would belong to society as a whole. However, since this isn’t very practical for everyone to be constantly controlling everything, the idea would be to establish management rights for resources or businesses in a form of a contract with the public. This would allow the public much more ability to step in and stop businesses that were doing things that were outright harmful to society, like underpaying their workers to the point of starvation, or exploiting a natural resource that could be more effectively be put to a different use.

This might sound radical, but it isn’t entirely too different from the way the natural resources on our public lands work today. For example, on a parcel of BLM grazing land, a ranching company will petition the government for the right to put cattle on the land; a public process will follow that allows the ranchers to make use of the land, and if there are any issues that go against the public good (e.g. the land is already overgrazed, or the methane released will increase global warming), representatives of the community can come forward to block access to the resource.

This is in contrast to a conventional capitalist relationship when a rancher owns their own land. Under a pure capitalist framework, the rancher would have the ability to do whatever they want with their livestock and land even when it’s detrimental to the public good. For example, they could overgraze a hillside to the point that it causes erosion, or they could treat their livestock with potentially harmful chemicals.

This is the change in framing of control between capitalism and socialism. In capitalism, the owner gets the final say, while in socialism, society gets the final say. In this sense, we already live in what’s called a “mixed economy,” where society has some capacity to regulate, but the rights of owners are also central to decision-making. To move in the direction of market socialism is just to negotiate where that fine line is between how much any individual should be allowed to control vs how much say society should have.

Rights to Profit

The second big thing about a market economy is the idea of profit. Individual companies make their decisions about production with the hope that they can sell their products for more money than it took to create them, pocketing the difference. This motive for profit would still be an important factor that would allow a socialist market to function. However, since the ownership of the company would ultimately be society as a whole, the profit distribution would no longer be to individual shareholders. Instead society would need to decide how to distribute the returns.

Now again, it would be quite difficult for all of society to decide where each dollar of profit goes, but it would be possible to set up rules for redistribution—to workers, customers, other businesses, and even directly back to the public-at-large.

Again, this may sound like a radical idea, but this has been carried out in several places (Norway, UAE, and Alaska), where profits from oil revenues have been nationalized and redistributed to all citizens. And in another form, described more carefully in the next section we’ll see how two specific proposals could manage this question.

A Specific Implementation: Economic Democracy

A particularly inspiring proposal for a form of market socialism is a system called Economic Democracy. There are several versions of this system, but I’m most familiar with the version proposed by Loyola University professor David Schweickart in his book After Capitalism, elaborated on and summarized afterwards. I suggest reading his whole book for a more complete picture, but I’ll explain the 3 main components briefly.

Regulated Market

The first element is actually very intuitive because it matches exactly with the system we already have, a regulated market for consumer goods and services. Basically, we all still go to the store or shop online for what we need to buy. The only difference would be the degree to which the government would attempt to regulate negative externalities either via price controls like a carbon tax or direct administration, like stronger laws for intentional disinformation. Overall this pillar of the current capitalist market would remain largely unchanged.

Democratic Workplaces

A much bigger change would be the establishment of democratic workplaces to deal with the control of businesses. As Schweickart describes it:

An enterprise should no longer be thought of as a thing to be bought and sold; an enterprise is a community. When you join the community, you get to vote.

The idea is that the workers at the company should have the best incentive to negotiate the pros and cons of business decisions since they will impact them the most. So instead of major business decisions being made by shareholders, based on share of capital investment, the major decision making would come from democratic vote by workers. This notion of economic empowerment for workers is a powerful idea that is most often encountered presently in the form of worker co-ops, though theoretically other institutions could operate with this same basic premise.

Public Control of Investment

This one might be a little less familiar to people who aren’t aware of how businesses raise investments today. Briefly, the way this works now, is people with significant savings will distribute their money to companies through any of a number of avenues, such as bank loans or public stocks or private equity firms. Under the Schweickart model, this system would be replaced with a system of only public banks offering grants to worker-owned businesses.

Personally, I find this last part a little too limiting2. I would think that there ought to be some form of heavily taxed semi-private equity that could be managed by people who have previously shown investment acumen. But I’ll hold off on elaborating on socialist venture capital for another post.

Socialism and Capitalism are Ideas

This article covered a lot and dove way into the details of a specific socialist implementation, but I want to make sure to step back and remind the reader that socialism, like capitalism, is just an idea. It never was a specific policy, but rather diverse set of philosophical concepts that come together to describe a coherent worldview for how to structure policy decisions. So thinking about how the world could work under socialism should always be an exercise that starts from understanding the broad principles before zooming into the minute details.

Remember that socialism has always been centered on society as a whole owning the economy, instead of leaving it to those with large reserves of capital. If you agree that its better for our economy to be controlled by everyone, rather than just those with a lot of money, you probably mostly agree with socialist ideas. And from there, it’s just a matter of figuring how we can achieve that goal in a practical way.

I believe that the conditions are in place for a migration toward market socialism, and if incremental steps to a market socialist economy are practical, it’s time we take them.

-

Not surprisingly there was a partisan bias, with Republicans still more likely to consider socialism to mean the government controls everything. ↩

-

To be fair, Schweickart also talks about an entrepreneurial capitalist in market socialism too. ↩

will stedden

will stedden